First Half-Century of Electronic Literature at Brown

First Half-Century of Electronic Literature at Brown

Script of Presentation by Robert Coover and Bobby Arellano

Origins

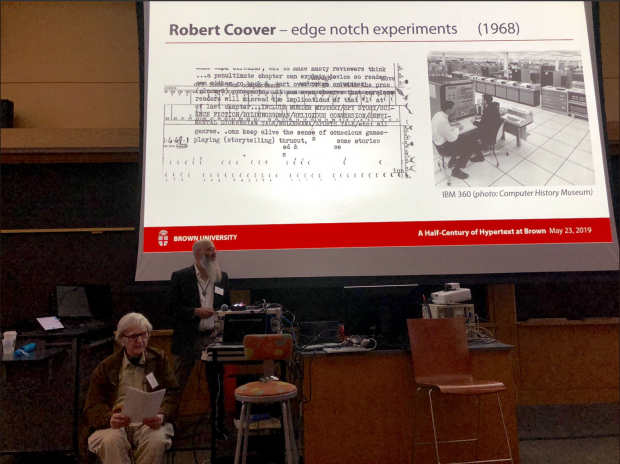

Once upon a time, in that mythical epoch known as the ‘60s—two or three years after the appearance of Julio Cortázar’s influential nonlinear novel Hopscotch—I started playing around with edgenotch cards, imagining a labyrinthine novel made up of a thick deck of such cards, punched in such a way that readers could, choosing their own routes, needle out sequences all held together in what now I would call a webwork of nonlinear narrative. It was, in effect, a primitive hypertext system, but with its elaborate thesaurus and attendant mechanisms, the coding and punching became numbingly tedious. Moreover, there was no likely publisher for such an eccentric enterprise, so, though I continued to use the edgenotch cards for note-taking for some years thereafter (I had bought boxes of the damned things, and had to use them up somehow), I returned to paper for the fiction writing and the delicious constraints of the page-turning book, which hyperfiction artist and novelist Shelley Jackson has called “an odd machine for installing text in the reader’s mind, though it too was once an object of wonder.” Shelley, perhaps the most innovatively talented of all Brown graduates, has a gift for the aphorism. “Hypertext,” she has said elsewhere, “is the banished body. Its compositional principle is desire. It gives a loudspeaker to the knee, a hearing trumpet to the elbow… Hypertext is the body languorously extending itself to its own limits, hemmed in only by its own lack of extent.”

What the edgenotch system diddo was soften me up for the hypertext applications being developed at Brown, from Andy Van Dam’s earliest experiments with HES—the Hypertext Editing System—and FRESS—the File Retrieval and Editing SyStem—to Brown’s creation of the elegant hypertext authoring system Intermedia. For HES, Andy had as a principal collaborator Ted Nelson, author of the influential book Computer Lib/Dream Machinesand coiner of the then-quasi-magical term “hypertext,” which soon provided the very grammar of the Internet. Nelson, who sees himself as a literary romantic, found in Vladimir Nabokov’s classic novel Pale Firewhat he has called “a real hypertext,” and while at Brown, actually prepared a stage script of Pale Fire, using his and Brown’s new Hypertext Editing System, to present on-screen to IBM, with the hope of getting funding for a very different sort of movie, or at least for an opening light-pen link to the industry. IBM never saw it, the presentation was never made, and the script itself disappeared into Brown’s files, until Norm Meyrowitz recently discovered the typescript, buried in an unvisited library vault: (“IBM Demo: Oral Script & Stage Directions.”)

It was George Landow, one of Intermedia’s developers, creator of the Victoria Web, and author of the landmark book Hypertext, who lured me into teaching my first hyperfiction workshop, using Intermedia, in 1991. As far as I know, it was another Brown first. Soon there would be open access to the WorldWideWeb, but at that moment it was closed to commoners like ourselves, and we were still a couple of years away from browzers, so the course was located in room 265 on the second floor of the CIT building, where the Intermedia server was uniquely installed. That was where published writers like Andrew Sean Greer, Will Oldham, Matt Derby, Mary-Kim Arnold first played at electronic interactive fiction.

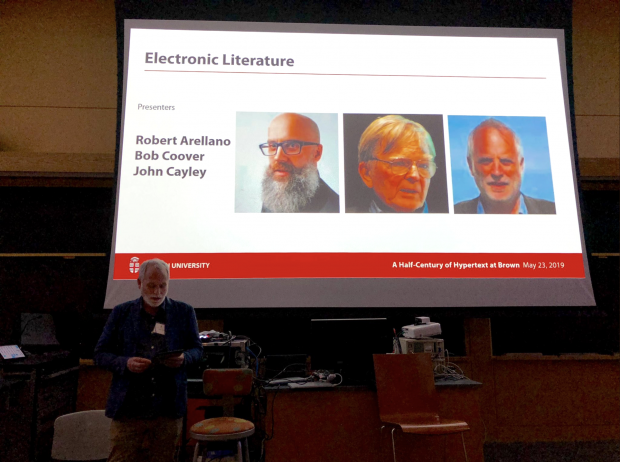

I was then strictly a DOS user and had never had a mouse in my hand—except for some white mice I once helped to rescue from my high school when it burned down back in the 1940s—and I thought a window was something you opened to let the hot air out, not in; so I obtained the services of an undergraduate T.A. who had learned Intermedia in one of George Landow’s courses. That was Robert Arellano, also known on the Net as Bobby Rabyd, who’s here with me today, now a fully bearded tenured professor in the Oregon wine country.

We were both enthusiasts of the new digital medium, Bobby actually producing a graduate student thesis called “Altamont” that, rechristened Sunshine ’69, became the first full-length hypertext fiction on the Web. Over the years while he was still at Brown, as a graduate student and later an adjunct lecturer, he and I taught what we called “hyperfiction workshops,” eventually upgraded into “electronic writing workshops,” and using as our software, with Intermedia suddenly defunct, Eastgate System’s Storyspace, created by Mark Bernstein. In those days we did a lot of traveling, spreading the word about Brown’s digital literary art workshops across the U.S., Europe, and Latin America, on campuses, in city libraries, and at literary festivals, including a memorable Christmastime demo in Sweden, where we found Intermedia still running on an old Unix in an art school in Stockholm. Bobby ran at Brown a famous festival of Cuban writing, Crossing the Line, sending the writers back to Cuba with the software and a lot of new ideas, and we always tried to include a digital component in our “Unspeakable Practices” series of innovative writing festivals.

The End of Books and TP21CL

I was doing a lot of straight-up book reviewing in those days for The New York Times Book Review, so they gave me a bit of space to talk about hypertext in a 1992 piece, written immediately after my first workshop, which they titled “The End of Books.” It became a hot ticket in the letters-to-the-editor column, so when I told them I’d like to review all known full-length hyperfictions while such a task was still possible,something unimaginable in the printed book technology since some time in the 1450’s, and very soon to become, as the World Wide Web became accessible to all via what were called “browsers,” impossible on the Net as well. They generously granted me seven full pages of the Book Review, including the illustrated front page. That summer 1993 piece was called “Hyperfiction: Novels for the Computer,” and included, not only an extensive review of Stuart Moulthrop’s new Victory Garden, destined to become a hyperfiction classic, along with Michael Joyce’s afternoonand Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl, but also a detailed overview of the form and its technology (“And Hypertext Is Only the Beginning. Watch Out!”) plus a review all the then-known full-length hyperfictions (“And Now, Boot Up the Reviews”). That was also the year that we took the Provost and a team from the President’s office on what we called a “Hyperland Tour,” a long hike from electronic node to electronic node on campus until we reached the more-or-less abandoned ground floor of the Grad Center, and there we laid out our plan for a multi-workstation facility for courses in the arts and humanities. The Provost wasn’t certain that computers were here to stay, but the President came up with the funding that created the MultiMedia Lab and adjoining fully-equipped classroom.

As the millennium began to turn, my friend Jeff Ballowe, recently retired as publisher of PC Magazine,with all his many tech industry connections, invited me to dinner in London, where we got up the idea of a conference at Brown on the new digital technology, one whose central aim was to bring e-writers and tech developers together for the first time. This became Technology Platforms for 21stCentury Literature, or TP21CL, largely funded by technology companies, thanks to Jeff, and held at Brown in April of 1999. Among the invitees was Scott Rettberg, who was there along with his coauthors to entertain us with readings from their funny award-winning hyperfiction “The Unknown,” and at a lecture in the old Duke Ellington Room in the Grad Center, now the Grad Student Lounge, Scott leaned over and asked me if it wasn’t time to launch an organization of e-writers. A brief conversation with Jeff Ballowe, and the Electronic Literature Organization, which has grown to be a vast international organization, was born, here on Brown’s campus, with Jeff as its first president and Scott its first managing director.

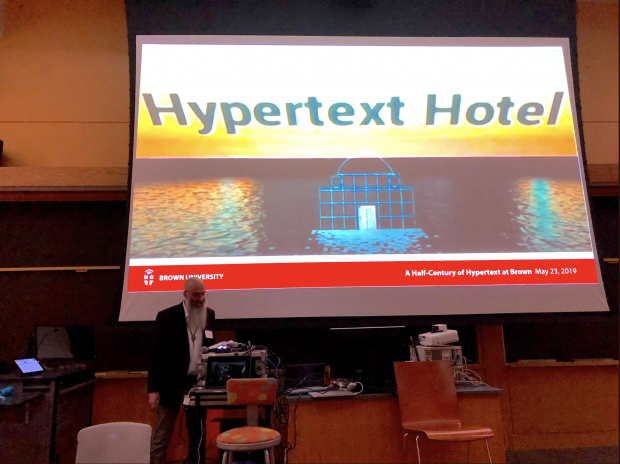

The Hypertext Hotel and Virtual Reality

When we launched the hyperfiction workshop in 1991, a year before the demise of Intermedia, we wanted a space where all class members, indeed any visitors as well, could interact freely. So we opened, at the very first workshop, a group fiction-writing space called “Hypertext Hotel.” Here, writers were invited to check in, to open up new rooms, new corridors, new intrigues, to unlink texts or create new links, to intrude upon or subvert the texts of others, to alter plot trajectories, manipulate time and space, to engage in dialogue through invented characters, then kill off one another's characters, or even to sabotage the hotel’s plumbing.

The Hypertext Hotel soon filled with multitudinous guest rooms, bars and restaurants, convention halls and ballrooms, a health club, a swimming pool and a golf course, a library, not to forget the roof and basement, where much of the stranger action took place. One of the Hotel bars, the Hurricane Lounge, became home to salesmen, musicians, including the Beatles, ladies of the night, frustrated writers, young girls running away from home, randy waitresses, a piratical ghost, and other beings even more out of the ordinary. A tall-tale-telling adventure group held their annual convention in the Grand Ballroom. The writers at the Original Voices festival of innovative women writers all gathered in the Hair Salon to have a go at dropping gossipy tales, and sins could be confessed in the Chapel, its services conducted by the resident chaplain, Rev. Mock Amerika. Naturally, there were repetitions; too many bartenders, for example. Whereupon, one writer responded by linking all the bartenders to Room 666, which he called the “Production Center,” an imprisoned alien monster was giving birth to full-grown bartenders on demand. Problem solved. One of them, anyway.

As you can tell, I’ve had a lot of fun with the form, and in particular with the group interactive nature of the Hotel, and its gift of anonymity. I know that Bobby is happy with the entries he has made to Room 212, for example, but I myself have tampered with them, and I assume I am not alone. I must say that working alongside Bobby Arellano has been one of the great pleasures of my life, lived mostly in writerly isolation. I first met him when he came to my office to ask me to supervise his undergraduate thesis. I told him I was paid so little, I didn’t have to do that. In the course of our conversation, I learned that he had learned Intermedia in a course with George Landow, so I told Bobby I was planning to teach the first hyperfiction workshop and asked him if he could TA it. “Sure,” he said. “If you’ll be my thesis advisor.” Bargain struck. Since then, the Hypertext Hotel has enjoyed many iterations, the most recent being the VR version being developed by Bobby and his students at Southern Oregon…

o o o o o